There is a fundamental difference between myth and story. Myths are mostly supernatural; stories are mostly fictional. Myths can generate powerful monsters, and they arise in every culture all around the globe. These mythical monsters are significant, because they are almost impossible to chase back into the shadows that they sprang from. They linger, refusing to depart. Perhaps we do not even want them gone.

Unlike myths, most stories are fictional. Others, like historical novels, can be based on legends or on facts, but the monsters stories yield, as every mother tells her children, are not real. Doctor Frankenstein’s monster is not real. This does not mean that the myth’s monster is more real, but myths give their monsters a supernatural quality. Sometimes, weird things happen, and a story seems to blend into a myth. In such cases, the monster of the myth becomes both supernatural and romanticised. Like some sort of chimera, it morphs into something even more outlandish than a legend or a myth. This combination of story and myth sometimes happened in the cases of Greek gods, so often based on real people, even if history preserves the memory of the myth above the man. But in other cases, the legend spirals up into a mushroom cloud of terror, as in the case of the legend of the vampire in the person of Count Dracula. Part man, part mythical monster, Dracula does not want to go away. He has become, by all accounts, immortal.

Authors love myths. So do filmmakers. Who could forget Francis Ford Coppola’s superlative portrayal of the volatile, seductive Count Dracula in the1992 film based on Bram Stoker’s controversial novel, Dracula? The novel took Victorian England by storm in 1897 when it first came out, and before long the filmmakers tapped into it. The horror movie gained ground, ramping up the fear that the book had opened up. But Stoker had based his character on a real person, Vlad III of Wallachia, whose statue sits in the town square of Bucharest where he is hailed as a national hero for fighting off the Turks in the fifteenth century. So which came first, the man or the myth, and why was he so popular?

We tend to think of Dracula as a monster rather than a national hero, a Gothic fiend brooding in his castle, which was how Stoker portrayed him. Stoker came across a book about Vlad’s turbulent family history in the library of the small, seaside resort of Whitby where he was holidaying at the time. There he read the stories – dark ones, ghoulish ones, of Vlad III impaling his enemies on spikes, holing himself up in his castle like a hermit, terrorising his enemies and giving the invading Ottoman army the greatest run for their money that they had ever had. All of this was, undeniably, true. But those were cruel times. Torture was commonplace; crusaders had been hardened by the sword. But still, no man was immortal and no woman either – or were they?

Eastern Europe is often seen as the heartland of the vampire persona. Stoker’s vampire, like Vlad III the man, had an Eastern European pedigree. He was an aristocratic fiend, a Prince. He did save his people from the Turks but he was part of a system that had grown into a monster, rather than a man that had become one. Eastern Europe was slow to break free from the shackles of feudalism. This aristocratic sucking of the feudal blood, the life-blood of the people, projected people’s deepest social fears onto the idea of the vampire, already deeply rooted in the folklore of the region. But there is another reason for the presence of the vampire in the culture of Eastern Europe. Immortality was an ancient Eastern European cult. Before Christianity came to Eastern Europe, and particularly Wallachia, which is present day Romania, immortality was real. The vampire in the shadows could not die; he lived on in the hope of a redemption, something that would pull him back to life. Perhaps it was love, perhaps it was remembrance. Sit down at a table where a family member passed away a year ago and they would be laying out his cutlery in anticipation of attendance. You may call that fear, or you may call it hope, but there was always a duality: dark and light, life and death, love and destruction. Such ideas have their origin in the beliefs of the old Goths, a religion that was mostly Manichaean. We still feel its presence in our culture. Good and evil battle side by side, even in the heart of every one of us. And that is what gives Dracula his mythical monster status. More than just a monster, he embodies both our fears and our dearest hopes of victory over death. Tormentor and seducer all wrapped up in the legend of one man. No wonder he’s still with us.

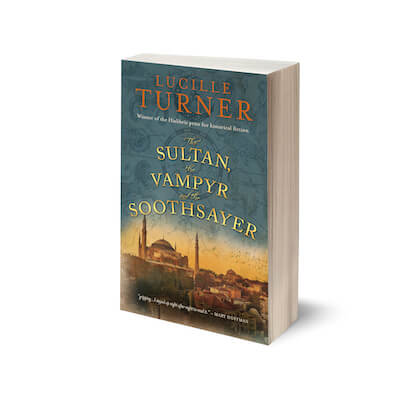

Read more about the vampire myth and the real Count Dracula in THE SULTAN, THE VAMPYR AND THE SOOTHSAYER HERE