What is Happiness?

People have been engaged in the search for happiness for a very long time. Identifying what makes us happy has preoccupied us for millennia. It is a subject that connects deeply with our sense of purpose. Is happiness the ultimate purpose of life, and if it is, how do we achieve it? Treatises have been written about it; people have dedicated their lives to the pursuit and understanding of it.

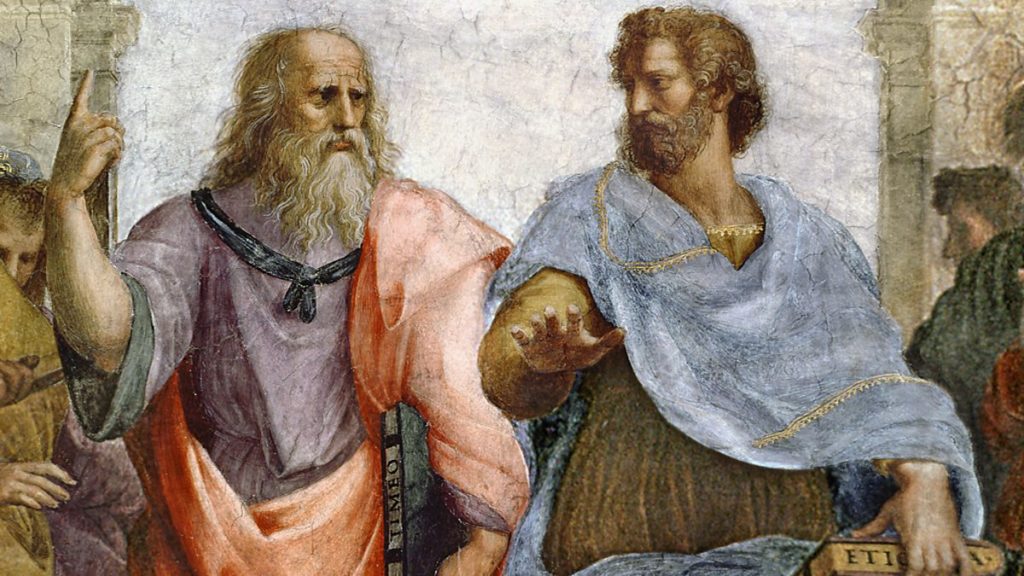

Aristotle spent most of his life wondering what happiness was. In the end, he concluded that happiness was about living up to your full potential as a rational human being. He threw out pleasure seeking and excess, and gave us the concept of achievement. Other Greek Philosophers such as Socrates, the father of Western Philosophy, also warned against the dangers of excess. ‘The secret of happiness,’ said Socrates,’ is not found in seeking more, but in developing the capacity to enjoy less’.

The warning went unheeded. Contemporary society has been built upon consumerism, and consumerism tells us exactly the opposite. We have to live for the moment, enjoy it while it lasts, have our cake and eat it. Even current political thinking is geared towards the sweet benefits of progress, and the cake is forever being doled out as the solution to misery, although perhaps the portions are not always equally distributed. Still, the key word is progress, and we have been dining off the word for such a length of time that we have almost forgotten what it actually means.

What is Progress?

For a very long time, progress was seen as the social path to happiness, but lately the notion of progress as a force for good has been discredited by historians and writers such as Jared Diamond, who in his book Guns, Germs and Steel claimed that the agricultural revolution, far from being a milestone of progress, was responsible for centuries of misery, subjugation and hardship. He called it, ‘the worst mistake in the history of the human race’.

It’s a sobering thought that ideals held up as the foundations of human civilisation can suddenly be so profoundly brought into doubt. Have we really been labouring under the illusion of progress as happiness for the best part of our history?

The industrialism, capitalism and consumerism that followed the agricultural revolution have continued to impact on ideas of human happiness. We are bombarded by advertisements focussing our minds on pleasure, and most of our industry has grown up around it. We need to buy the new phone, play the new game and buy the new car in order to be happy. Consumerism depends upon this model of happiness, and we as a society have been pumping it out for decades. It’s not about enjoying less, but enjoying as much as possible. What has been the cost, in real terms?

The Price of Progress

As ever, history provides the vital clue. Aristotle was possibly the greatest philosopher of his time. He is still revered. His contributions to science, politics and ethics are undisputed. But the power of many of his arguments was based on one fundamental conviction: that human beings were superior to every other creature on the planet. Humankind was rational; animals were not. And this rationality was the key to our God-given right to be happy at the expense of every other living thing. Aristotle was nothing if not rigorous; he distinguished five hundred species of birds, mammals and fishes, and classified them. But he still came to the conclusion that their instincts were base and our consideration of them must be defined by our own more important human needs. We needed to be happy; they did not.

This idea of human beings as virtuous and deserving was understandably popular. Aristotle’s thinking was taken up by Thomas Aquinas and incorporated into Christianity. There, it was given the sanction of divinity. But was it actually true?

The Human Right to Happiness

For centuries we have seen ourselves as the chosen ones among the rest of creation. We have anchored these myths into the bedrock of religion right from the start and they are hard to pick apart. We don’t care about other animals and the environments they inhabit because only we, as rational animals matter, and so the rest of the animal kingdom can be tested in laboratories, killed in any way that suits our needs, and ultimately sidelined in favour of our own implacable ascendancy.

These ideas are at last starting to be seriously questioned. One vital part of the ascendancy of human welfare over animal welfare has been the existence of a soul. Aristotle intellectualised the human soul, thereby discounting the souls of animals. No intellect? No soul. Only those creatures in possession of a soul could have a chance of happiness in any real sense. So, do animals really have no soul or have we just painted it out of the picture?

The Primitive Soul

Often, you need to travel further back in history in order to step back from it. Before the Greeks came along and built their civilised societies, which have been the inspiration of our own, people had existed differently. You can see the echoes of these long forgotten lives in other native cultures, which have been driven to extinction more recently. Native American Indian culture is full of the souls of other animals. Ritual, both as ceremony and acts once protected the hunted from the hunter. The hunter could use the animals, but he was bound by ritual to protect them. The same way of thinking attached him to the land. But it’s not as if we can turn back the clock. People’s expectations have evolved somewhat since the days of the hunter-gatherers. So what’s the answer?

A New Path to Happiness

We could just lower them? American Author Henry Thoreau said in the middle of the nineteenth century, “Happiness is like a butterfly; the more you chase it, the more it will elude you, but if you turn your attention to other things, it will come and sit softly on your shoulder.”

This could be a good idea. We could spend less time thinking about our own pursuit of happiness and more time thinking about what we could do better, or what we could change. Change is currently being practised by millions of people around the globe in the wake of the recent pandemic. Expectations too seem to have been lowering as people do without the things they once thought that they valued. So, have we already taken the first step on the path to global happiness, and will we all be fit to stay the course?

Fascinating article, thank you. It is interesting to contemplate progress and happiness, both together and separately. There is little doubt that some progress relieves an enormous amount of misery – for instance the eradication of smallpox. But is the absence of misery the same as the abundance of happiness? I suspect not. If you saved an animal’s life, would it be happy?

This is the type of article that really sets you thinking!

Thanks Chris…interesting comments!