THE DEATH OF A GENIUS, THE BIRTH OF A LEGEND

On the 500 year anniversary of Leonardo’s death, we are drawn to re-imagine the scene in the chateau of Amboise where he died in 1519, recumbent on the small bed in the room above the river, with the French king Francois looking on despairingly. The death of Leonardo, like the passing of other great, iconic personalities, resonates through time. Pausing in the bedroom of Amboise, you cannot help but ask yourself the question: How could such a genius at last become extinct?

Leonardo da Vinci was a major player in the evolution of human understanding. Few men incarnated such a strong, early connection between art and science as he did, and yet Leonardo painted relatively little. Much of his time was spent on invention and discovery. And as with everything he set his mind to, Leonardo was the kind of man who left no stone unturned. He was obsessive to such a point that he was almost unemployable. He gained a reputation as a procrastinator, but in reality he was probably more of a perfectionist. Either he did a thing his way, or he didn’t do it at all. His painting of Saint Jerome in the Wilderness was left unfinished. The Adoration of the Magi was abandoned. His fresco of The Last Supper was applied almost as an experiment, and the fresco started crumbling soon after it had dried.

This uncompromising, apparently capricious streak did nothing to help Leonardo’s finances. Poverty dogged him for much of his life, pushing him into the clutches of men like the Duke of Milan, and Cesare Borgia, both of them demanding, difficult and dangerous men. He swam against the current of his day when he attempted to understand the order of the world empirically, rather than in creationist terms, and his work was not always sacred enough for the standards of his time. He was almost excommunicated at one point for carrying out dissections on human corpses, and that would have meant even fewer commissions. But despite all these apparent obstacles to success, Leonardo created what is largely considered as the most enduring masterpiece of all time, the portrait of a woman known as Mona (Madonna) Lisa.

Giorgio Vasari, who wrote about the lives of the great Renaissance men about fifty years after Leonardo’s death, says he remembered seeing Leonardo working on a painting of a woman with an interesting background. The subject, as we now know from letters recently discovered that reveal the identity of the sitter, was Lisa Gherardini, wife of Florentine silk merchant Francesco di Zanobi del Giocondo. And so the portrait of La Gioconda was born. In Italian, the name means laughing or playful one. It is a good play on words, even if it does not express all the complexity of the Mona Lisa face. Vasari saw this complexity – he noted how, ‘in the pit of the throat, if one gazed upon it intently, could be seen the beating of the pulse’, a comment that foreshadows future observations, namely that the eyes of la Gioconda follow you, or that her smile is an enigma — one moment you see it, the next it disappears.

Vasari had his small part to play in seeding the mystery of the Mona Lisa, but Leonardo fuelled the myth himself because he kept the portrait closely guarded at his side for years, and refused to deliver it to the man who had commissioned it as a wedding portrait, Francesco del Giocondo. Wherever he went, Leonardo loaded the painting onto his cart and trundled it off with the rest of his luggage. By the time the painting arrived in France in 1516 it was quite well travelled. By then, Leonardo had worked on it for almost twenty years, layering his paint on in fine applications until the portrait gradually acquired the depth it still has today, in spite of its age. But there were other things that contributed to the mystery of the Mona Lisa as well as her non-delivery, and one of them was connected to a sort of Leonardo fallacy, which was reinforced by Dan Brown’s Da Vinci code.

In The Da Vinci Code Leonardo is said to have been a member of the Sanhedrin: an order connected to the Knights Templar and the Rosicrucians. The trail from the Rosicrucians leads back to the pre Christian era, and the tenets of Hermetic belief.

The beliefs of these orders are inherently secretive, and in reality owe their origins to the ancient Mystery Schools and Gnosticism. The Knights Templar were originally formed as guardians of the Holy Grail: the cup that was said the have been used by Jesus during the Last Supper. In The Da Vinci Code it was the nature of the Holy Grail that caused the sensation: person not cup. The grail was therefore symbol rather than object. The link to Leonardo resided, for Dan Brown, in the theory that Leonardo’s work was rich in symbolism, or to use a Dan Brownism, that there existed a ‘Da Vinci code’.

Before we all get out our decoders, the difference between a code and a symbol is worth thinking about. A code is a piece of information, which has been deliberately hidden and needs to be deciphered. A symbol, on the other hand, is a representation of something else, which can be understood through a process of association and identification. It would be more accurate to say that Leonardo’s art contains symbols rather than codes.

It could also be said that the painting of the Mona Lisa owes its fame and enduring quality to the symbolism embedded within it. We see a woman sitting on a balcony against the backdrop of a view, smiling. On the surface of it, there is nothing particularly extraordinary about that. So, why all the mystery?

Perhaps the mystery lays not so much in the woman herself as in the associations she provided. From Leonardo’s perspective, these associations form the fabric of the painting. They are the link between Lisa and her background, Leonardo’s particular connection between science and art.

By the time he painted the portrait of Mona Lisa, Leonardo had understood how the eye works, and peripheral vision in particular. He had also understood that the brain receives the images we see upside down, and that it corrects these images. In short, he sensed that what we see is not exactly the whole picture. Sight must be processed; the old rules of linear perspective, which had marked the art of pre-Renaissance Italy so strongly, were incorrect. The three dimensional image that we see is recreated essentially in the brain, not in the eye.

How likely would it have been that Leonardo brought all his discoveries to bear in one painting, and that the painting in question was Lisa’s portrait? Quite likely. The eyes appear to move, to look in all directions at one time. The smile is ambiguous, dependent on who is looking and where they are looking at any one time. But it could also depend on how they are using their peripheral vision.

The power of peripheral vision is like a juggling act. The juggler can only keep going if he uses peripheral vision. The moment he focuses on one ball, instead of all the balls at once, the spell is broken and the balls fall. Apply this to Leonardo’s portrait, and the same process is at work. We focus on the smile and it vanishes. We focus on the face and it reappears. We focus on the eyes, and the smile vanishes again. We step back and focus on nothing at all, and the smile is there again. When Leonardo painted Lisa, was he giving us peripheral vision in a portrait? Does he force us to use our peripheral vision when we look into his painting?

The idea that Leonardo has painted the secret of sight in Mona Lisa is an entrancing one, but there is more to his painting than one ambiguous expression. There is also the background.

It would have been common practice at the time in portrait painting for the artist to use a simple background of drapes or flowers, but Leonardo preferred something a little more spectacular. Was Lisa del Giocondo aware of the mountainous, primeval landscape being conjured at her back when the portrait was being painted? But since Leonardo had no intention of delivering it anyway, did it really matter? Rivers were being formed and mountains were being made behind Mona Lisa’s back. What did Leonardo intend by it?

To understand the background, we need to view Leonardo and his painting as one complete whole. Someone who is curious about the natural world, as Leonardo was, will be curious in his work, and this curiosity has given the painting its air of almost supernatural mystery. The slow work of time is depicted in the background, and in the layers of the painting — layer after layer over a period of years. Now, five hundred of those years have passed, and we continue to wonder how he did it. Now that, is genius.

Receive the next instalment directly in your inbox

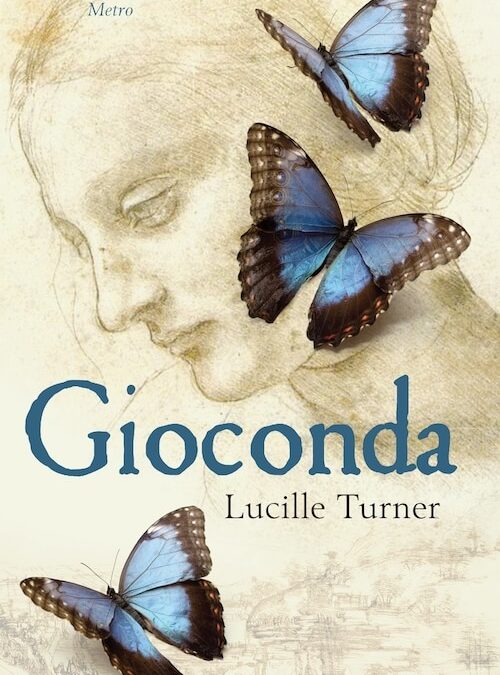

Buy books by Lucille Turner MORE HERE

A Novel about the Life of Leonardo Da Vinci

Buy it HERE

Hello! I’ve been following your web site for some time now and finally got the courage to go ahead and give you a shout out from Austin Texas!

Just wanted to tell you keep up the excellent work!

Thank you so much, Austin Texas!