Over the past two hundred years most monarchies in the western world have died out, some violently, as in France and Russia, others more peaceably as in the case of Spain. Those that still remain – ancient dynasties such as the Danish Royal Family – keep a relatively low profile by comparison with the British Royal Family, who unlike some of the remaining European monarchs cannot shop at the supermarket. The British monarchy continues to have a major international presence, both in Britain and the Commonwealth. Security is high in Britain as far as the first Royals are concerned, and public appearances are played out according to centuries-old protocols. The recent hotly discussed interview by the Duke and Duchess of Sussex surprises us because it goes against old codes of behaviour unchanged for centuries – with thou shalt not gossip being traditionally one of them. Whatever your opinion is of the endless royal saga of unions and faux pas, the royal family is not easy to modernise, and fortunately or not – depending on your view – it is nigh on impossible to dismantle.

In 2020 62% of people in this country supported the monarchy, while in 2012 it was 80%. Of course this is a significant drop in support, but it is still a clear majority. How that will change when our current Queen passes away is unclear. People in other countries often ask why we in Britain continue with our Royalist tradition. Is it that we still want to feel like the empire building monarchic power of bygone days? Are we clinging on to something that has ended, a colonial past, which had Queen Victoria reigning over a quarter of the world from a small group of rocks in the North Sea called Britannia?

Younger generations might prefer to move on. Some are only dimly aware of the history, and others do not even see the need to continue with all the pomp and circumstance. But we should remember that beneath the layers of our history lies something quite significant: identity. We often talk about individual identity, because individuality is important to us, but national identity has become a dangerous word with its overtones of nationalism and its sinister motifs of exclusionism. It could be argued whether, in a global world, we even need a national identity, but I believe we do. Without a national identity our institutions would be under threat. Anarchy could take the place of monarchy and the monarchy is as much a part of our national identity as the idea of fair play, or the weird, quasi-repellent odour of Marmite. It is the Beefeater standing in our sitting room, a reminder of our history and traditions. If we did not have a monarchy, what would we replace it with, a dictator, political doctrine, or a new kind of sandwich spread?

William the Conqueror, who returned to claim the English throne in 1066 after the death of Edward the Confessor is the forebear of the present Queen Elizabeth and the British throne has been hereditary ever since. To question the right of kings and queens to rule lies at the centre of anti-royalist sentiment, and the lax behaviour of the ‘lesser’ royals may make us wonder why the right to rule has to rest with just one single unelected family. In 1642 we did more than wonder, we fought the matter out.

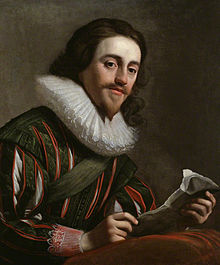

This was a time in our history when we didn’t want to replace the monarchy with anything, except perhaps parliament. The English civil war began in 1642 and ended in 1651 with the execution of Charles I. This act, never before or since seen on these islands, was carried out on the steps of the royal palace of Whitehall. It effectively marked the end of the sovereign’s divine right to rule, a right which meant that kings and queens derived their power from God, not the people they ruled. In France it led to absolutism and the Revolution of 1789. In England the right was called into question more than a century earlier than that. The outcome of the civil war was that parliament would henceforth hold the reigns of power. The monarch would no longer answer only to God, he or she must answer to the people. Of course, tradition meant that the ceremony of anointment continued to be performed by the Archbishop of Canterbury but royal prerogative, the ultimate power that the monarchs once held, was now de facto in the hands of parliament.

The English civil war was not as violent or as total as the French revolution. Heads did not roll far. Tradition and the monarchy were preserved because the Royalists simply would not go away. The Republic of England was short-lived but although Charles II was restored to the throne in 1660 his wings were severely clipped. When the royal palace of Whitehall was destroyed by fire in 1698, the heat had already been taken out of royalty and parliament would keep it ever after. Eventually Whitehall became synonymous with the seat of government not the residence of kings. Still, the monarchy was not entirely bereft of the power it once had. Today, the Queen cannot interfere with government but she does have the subtle powers to temper it. She could sack the Prime Minister if she or he did not secure the confidence of parliament, and so prevent individual ambition from impinging on democracy. She cannot choose a government, but she can certainly ensure it is legitimate. She can dissolve parliament and is the only person in the country who can declare war on another state. Her father did this at the outbreak of World War II, but Elizabeth II never has. This balance between the monarchy and parliament is the fruit of a thousand years of history, and as the mainstay of our liberty we would tamper with it at our peril. Identity matters, and when it is tarnished we have to wipe it clean and keep on going. The alternative is a country that threatens its future instead of building on the foundations of its past – and better to build on what is sound and solid than to blow the whole thing up.