The motivation for almost all warfare throughout history has mainly been either economic gain or territorial gain. There have been wars fought over religion, but even these have been fuelled by gain of some kind. The Second World War felt exceptional because there was clearly a greater evil to be fought, and conflict seemed morally justifiable, despite the huge numbers of innocent people lost. But even if, during the course of human history, there have been what we call ‘legitimate’ wars, these have served only to fuel a need for conflict that seems to be inherent in us. We glorify war, film it and write about it. Our greatest heroes act their parts against the backdrop of war; the theatre of war provides us with the pretext we need to live out the struggle between good and evil, which is inherent in our nature. History — both ancient and modern, shows us that we cannot eliminate war; the best we can hope to do is to control it. In order to do this, we have built democracy and elected governments, we have established the rule of law and tried to find the right men for the job. How successful have such measures really been?

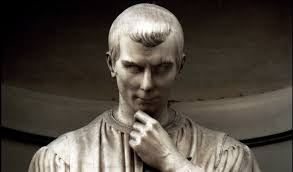

As the Church lost its influence after the Enlightenment, it was the state that legitimised war. The state is a relatively modern concept. There had been earlier states elsewhere in the world, such as Ancient Egypt and China, and the city-states of Ancient Greece wielded great influence. Rome was a superbly successful city-state, allowing the idea of one city to grow into an empire, but modern nation-states only rose up in Europe from around the fifteenth century onwards. After the decline of the Roman Empire, feudalism and the Church were the social structures that demanded the fealty of the people. Later they became superseded by monarchies, where kings and queens ruled by divine right, gradually becoming as powerful as the Church, and in some cases even shouldering it aside. But whether imperial, monarchic or republic, over the next three centuries virtually every region of the world became parcelled up into states in one form or another. The consequence of this pattern of change was that the idea of war became embedded in the idea of statehood, and one of the first people to make the connection between the needs of the state and the need for war was a man whose name has become associated with evil to such an extent that when we describe someone as being Machiavellian, we all know exactly what we mean.

Machiavelli, who is often called the founder of modern politics, is widely considered to be a paradigm of wickedness because of a book he penned in 1513, entitled, The Prince. The book can arguably be called a treatise on realpolitik, or politics with pragmatism. Machiavelli did not coin the term, realpolitik, but he certainly believed in it. He lived during the time of the Italian Renaissance, when the Italian city-states had, despite their power of innovation and creativity, sunk to a level of violence and warmongering that was really quite astonishing. When a cardinal sanctioned murder in a cathedral in Florence for political motives during the Pazzi conspiracy of 1478, it seemed like the final straw on an already high mound of dung-infested power politics. But that did not stop Niccolò Machiavelli. “In seizing a state,” he wrote, “the usurper ought to examine closely into all those injuries which it is necessary for him to inflict, and to do them all at one stroke, so as not to have to repeat them daily” — that certainly is pragmatic thinking. Perhaps Machiavelli was simply trying to defend the superior and beautiful city-state of Florence (and who can blame him for that), but his ideas sanctioned warmongering in the interests of securing control over another state, and people followed his lead.

In the nineteenth century Sociologist Max Weber defined a state as a system with a monopoly on the legitimate use of force within a specific area, and this concept became enshrined in public law through the policing of the state. In feudal times, the lord had the right to use force to secure his interests in the area he controlled, now that right had effectively been passed on to the nation. This did not give a state the right to use force against its neighbours, however, but it did not take politicians long to realise that the motive of self-defence provided the state, in the end, with all the justification it needed to use all the force it wanted, thereby putting Machiavelli’s most famous maxim to the test: the end justifies the means. If the end, or aim of war is self-defence, then it is seen as right. After all, what nation-state could base its policies on the Christian doctrine of turning the other cheek? The survival of the state would simply not permit it.

There were other holes too in Weber’s thinking. The security of a state depends also on its military power, and on the extent to which this military power can be checked. Modern nations have invested huge sums of money in weaponry and the military, but in doing so they have juggled with a double-edged sword. At no time was this more evident than during the Cold War. In arming ourselves for peace, we armed ourselves for war. All of which means that selecting the right person for the management of the state has never been so important. Equally important are the systems permitting us to make that choice, such as democracy. But even if we are so fortunate as to have those systems in place, we still need information.

In the modern era it is, arguably, only information that can save us from the dangers of war. We may never be able to eliminate war altogether, but with the breadth of information we now have at our fingertips, our best hope lies in understanding it.

Next Week: A Short History of Ideas looks at something more cheerful:)…